My name is Steve Dodson I’m a retired copyeditor currently living in western Massachusetts after many years in New York City. *That said, she reportedly remained illiterate (in any language) her entire life, which I know only because mentioned in a family memoir, and presumably mentioned only because (unlike the situation in most times and places in human history) illiteracy in adulthood for a white woman born in North America circa 1840 was, at least outside of a few geographical backwaters, so rare as to be noteworthy.Ĭommented-On Language Hat Posts (courtesy of J.C. (Washtenaw County, Mich.) in the 1860’s there was likely no one around with whom she could try to keep up her Gaelic except perhaps for some Irish-Catholic immigrants whose L1 may or may not have been mutually comprehensible and as to whom there might have been various sociological barriers discouraging seeking them out for language-maintenance reasons.

There were some Gaelic-speakers floating around parts of Ontario back then, but I imagine that after the family emigrated to the U.S. MacKinnon’s study were by then deceased.”Īs I may have mentioned, one of my great-great-grandmothers was in her earlier childhood in Cape Breton (she was born 1836 or ’37) a monolingual Gaelic speaker, but she was exposed to English once she started school* and eventually moved out of the community and married a dude from Ontario who was presumably a monolingual Anglophone. Monolinguals in Edward’s (1991) study which suggests that those still alive at the time of Heįound that the most capable Gaelic speakers were those who were the oldest, held semiskilled jobs, and were the least educated. Speakers and students of Gaelic from various parts of the province of Nova Scotia. Edwards (1991) conducted a study of three groups of Gaelic These monolinguals were comprised of a handful of women in their 80s and 90s “As late as 1976-1977, a few Gaelic monolinguals could still be found in rural Capeīreton. It’s a wonderful sound, and I wish the clip lasted longer.įound in a 21st-century Canadian grad-student thesis:

There may come a time in a few centuries where a lot of the distinctive features of Indian English have been naturalized in the same way, so that phonological transfer from Indian languages (which now strikes Americans or Britons as signs of imperfect English learning) sounds to them like nothing more than deep regionalism. English spoken with a heavy non-native accent by an Irish speaker can still, pronunciation-wise, fall within my sense of “what English-speakers can sound like”. It is not native Hiberno-English phonology of any kind, but it has enough in common with heavily Irish-influenced varieties of Hiberno-English that, if I heard somebody speaking with this *accent* today using native-like syntax, I doubt I would take them for a non-native English speaker. Sayers was not only a native Irish speaker but part of a generation which still contained Irish speakers who spoke English imperfectly (believe it or not the last documented monolingual Irish-speaker who spoke no English only died in 1998.) This is a recording of Peig Sayers speaking somewhat broken English.

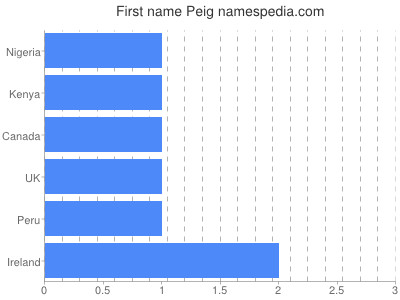

#Peig name pronunciation full#

This puts into perspective what I really mean when I tell people that Indian English (which now does have full native speakers) is just as much a part of English as Irish or Welsh English, and is similar to them in having substrate effects from other languages. Via Alex Foreman’s Facebook post, a YouTube clip (less than a minute long) of native Irish speaker Peig Sayers speaking English.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)